Accessibility overlays are good for business (just not yours)

Accessibility overlays are for suckers. But they are ruining the spirit and reputation of one of the best things about computers: personalization. So why do businesses love them?

Accessibility overlays are a terrible artifact of our current times. For those who stumble onto my blog and are unaware of what these things are, they are a piece of technology sold to businesses as a one-stop shop for all website accessibility concerns. The entire field of accessibility design and compliance can be solved with one simple, easy-to-swallow pill for only 500 bucks per year.

Yet, overlays consistently over-promise their capabilities, actually produce bad experiences for people with disabilities, sue people who write against them, reduce user privacy, and increase your own risk of getting sued for excluding people from being able to use your website.

And yet, businesses still love them (even people who I’ve shared resources with end up using them).

But to me, overlays are like Ivermectin for website accessibility. Instead of taking a vaccine, going to a real doctor, or practicing behaviors that reduce the spread of disease, Ivermectin (sold as a horse de-wormer over the counter) exploded in popularity as a method of dealing with COVID-19 (link to a NYT gift article on the still-popular craze of Ivermectin use).

Of course, Ivermectin doesn’t cure COVID infection or improve immunity against it either. But people bought Ivermectin like crazy during the pandemic (and still do).

I view accessibility overlays like Ivermectin: they are entirely a grift that enables people to continue to make bad decisions.

See, the thing about Ivermectin isn’t just that people chose to consume something that was entirely impotent but that consuming Ivermectin was a way to avoid actually making good decisions about COVID (masking, staying indoors, getting vaccinated, etc). And overlays ultimately, by nature of how they are marketed, enable website designers to remain ignorant about accessibility.

Nobody wants to admit this: overlays are successful because people are scared of accessibility work (and this is a real business problem)

Overlays operate with a really interesting pitch: “never improve your accessibility, that way we can keep making money off of you by doing it for you.” People love this. And honestly? The accessibility community might be a bit to blame for why this pitch seems to work. But first, I want to unpack the basic business proposition overlays make.

Isn’t it strange to pay a yearly subscription to a service that doesn’t permanently change anything? If you take a step back from website design and accessibility for a moment, ideally the model works like this: you build a website and then people use it. Websites might need occasional maintainence or updating, but most of the work that goes into them is during their initial creation.

But businesses love overlays. “Small to mids” (as we would say back at Visa) seem to be the target market for overlays. The big players like Amazon, Microsoft, Apple, Google, Netflix, and so on can’t risk something like an overlay. They have in-house experts doing things because overlays aren’t worth the litigation.

But smaller companies are terrified: litagation could destroy them. But they don’t know where to turn or how to solve something scary like “compliance” or “conformance.” Because these business owners operate from a position of scarcity and insecurity when it comes to accessibility, they are more likely to make the wrong decision. Unfortunately, the way scarcity affects our brains isn’t unique to business owners either; we just work this way.

By now (thanks to 2016 here in the US in particular) we have plenty of studies that demonstrate that economic insecurity is strongly associated with conservative, far-right, and populist voting patterns. When we get scared and insecure, we tend to end up with worse outcomes.

But I don’t argue that “people make bad decisions when they are scared” and that means it is their fault for getting scared but rather, I want to argue that blaming businesses is the wrong approach when it comes to overlays. Yes, a business ultimately makes the decision to use an overlay. And yes, they will ultimately be the one who gets sued when that overlay fails. But business owners are often worried about whether they can afford to do something the right way. And this creates an opportunity.

The financial opportunity is so great to overlay companies that they are willing to get sued and even willing to support their customers who get sued. They make that much money off of all this. Overlay companies like accessiBe have a whole support page where they try to assure customers that even if you get sued, we have enough money and resources to win.

And it is for this reason that overlays are the true villains: they aren’t just filling a business need, but a business fear. They are successful because doing accessibility the right way is scary. They’re taking advantage of the scarcity of knowledge and insecurity of small-to-mid business owners.

We are partly to blame for accessibilty fears. But I also want to stress that overlays operate in the same way that AI companies do. AI companies stoke fears about how “artificial general intelligence” will destroy the world if we don’t regulate AI. And guess who gets to regulate AI and contribute to policy and governance on AI? Those companies, of course.

In the same way, overlay companies benefit more and more when accessibility gets scarier and scarier. The more someone gets sued (who isn’t them) and the more that accessibility practitioners get on people’s cases? The better. They deal in fear; it’s good business.

Overlays are ruining my favorite part of computers: personalization

So all of this leads me to the thing that I actually want to talk about: overlays are ruining personalization.

Personalization, especially for accessibility, should be about setting up how you want a computer, game, or digital experience to work for you. I love the idea of personalization and have written about it for a while now. Personalization is at the heart of Apple’s accessibility with “make it yours” and was the motivation for my latest project, Softerware.

But personalization is a tricky subject. It requires the user to do a lot of work: they have to recognize that something about their experience of an interface is wrong, know what they’d want the interface to do, and then look for or discover how to personalize their experience to suit their needs.

Two of the fundamental UX problems with existing research in “malleable interfaces” and “end user programming:” it’s a lot of work to personalize and it can be hard to figure out how to do it.

The immortally brilliant Adrian Roselli wrote about the problem of “recreating what browsers already do” when it comes to widgets that increase text size, all the way back in 2016 (wild to think that was nearly a decade ago now).

But one of the major reasons that something as simple as personalizing text size can become an issue is because users likely won’t discover that the solution to their problem lives in a little widget somewhere. And guess what? Accessibility overlays hinge on this design. Their entire interface is hidden in a little widget.

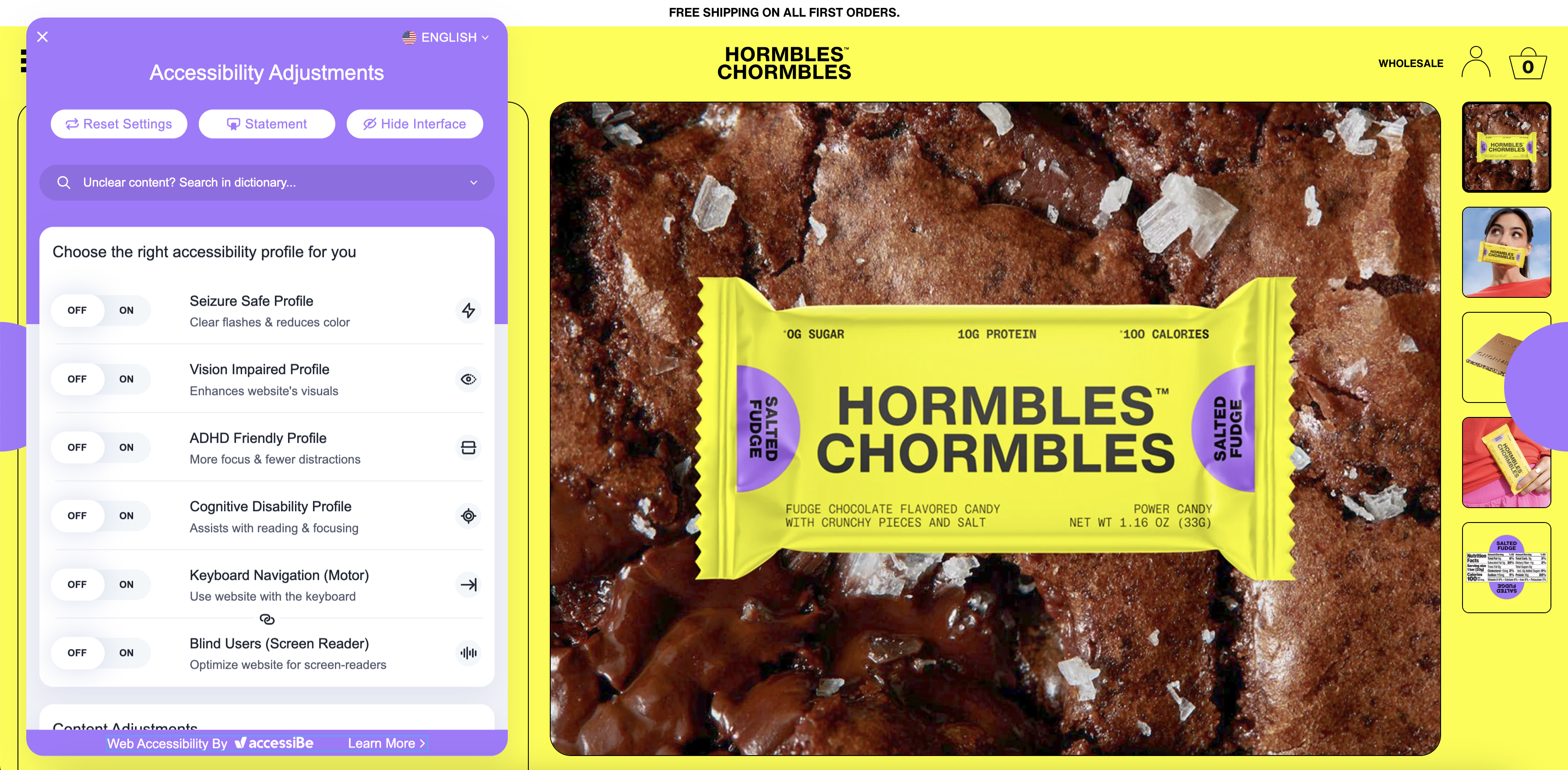

Just recently, I was looking up some kind of artificially-sweetened “candy” bar called Hormbles Chormbles and noticed they had an accessiBe overlay. When you click it, the following screen appears:

I think that a few things become a problem with overlays, but based on my research on Softerware, there is one very particular thing that I want to talk about: persistence.

Persistence, in terms of personalization, is the idea that you set something once and can forget it. This saves people time and effort and helps enforce your personalization interests automatically.

Overlays, like on the Hormbles Chormbles website, do save your settings when you re-visit the site. I select an option, close my browser, revisit the site, and the option is still chosen. “This is great!” you might think. But now I worry about my privacy: how did they save these settings? And where?

One of the best parts about how the web is currently designed is that privacy is paramount and seen as a fundamental human right, especially for people who have disabilities and/or use assistive technologies.

So how do they track my settings? And do I want a company knowing that I perhaps chose a profile for “seizure-safe”? This information should, ideally, remain private. Users of social media who have epilepsy have been attacked in the past with seizure-inducing gifs. Private information about your health could be used in all kinds of damaging ways (beside this one example).

So privacy-preserving ways to have persistence of personalization profiles is important (wow, talk about alliteration there).

So overlays are probably using cookies, even though I wasn’t asked about which cookies I’d want to save on the website. (And cookie-consent interfaces are already a whole mess to untangle in our modern age.)

But to make matters worse, overlays don’t have persistence across domains. If I change some options on Hormbles Chormbles and then go over to Data Literacy, those options don’t follow me. What a massive waste of my time and effort.

And of course, overlays don’t share data with other overlay companies (which would be a nightmare). Userway, audioeye, and accessiBe are some of the more-notorious overlay companies, but there are actually quite a lot of different companies that offer overlay-like solutions. All of them offer different user experiences, capabilities, and methods for “automatically” making something more accessible. Getting them to play nice with each other is probably impossible (since historically this rarely happens between competitors).

I think that overlay companies don’t really care whether or not their product actually gets used, they just want business owners to buy it. Adrian Roselli wrote in 2016 about his own work on text-size widgets: people don’t use them at all.

And why would they? How often do I go to a website, stay on it long enough to figure out that the design is painful, look for (and manage to find) a way to alleviate that painful design, and then adjust that design to fit in a way that actually works for me? Again: overlay companies don’t care about the fact this user persona doesn’t exist in real life (a persona-non-est, if you will). But business owners also don’t care if the persona exists or not because that is precisely why they paid someone else: they want an accessibility service to do all of the design thinking and solutioning for them so they don’t have to.

So overlays do take and monitor your data, to some degree. But they don’t even do it in a way that saves you time and energy: you have to constantly re-discover and re-perform the labor of fixing a website. And of course, the solutions they offer in the first place are often entirely impotent.

Why personalization is actually, despite overlays, still awesome

This leads me to my work on personalization and my own interests: I first fell in love with computers because of personalization. I built my own desktop computer when I was 10 or so: I picked the parts, bought them myself (with my paper route money from my job my mom got me illegally), and assembled it on my own. Since then, I’ve been obsessed with computers.

Of course, that was hardware personalization. The cool thing about hardware is that it’s harder to change after you assemble it. That means your choices up front matter, but also tend to have longer-lasting impact. One set of decisions could last 7 years, if I take good care of that machine. That rules.

And looking over to Apple again, their philosophy for accessibility is still the correct one: we should make our computers ours. You can’t have personal computing without personalization.

One of my favorite pieces of all time is by Hickman and Hagerty, “Standardized access: the tension between scale and fit.” And good accessibility is, as they write, about fit. Something that fits perfectly, would be a well-tailored, highly personal artifact or experience. But doing this work takes time and energy, which is why it is always in tension with scale. Scale doesn’t have time to solve every issue for all people, so it shoots for means, averages, and majorities whenever possible. Scale doesn’t care about the margins.

So why is personalization of hardware, an operating system, or in award-winning video games, somehow better than personalization of a website, using an overlay? Well, because overlays have applied personalization to an impersonal context. This is because overlay companies are far more interested in scale than real access. They have money to make.

So let’s revisit Apple’s motto “make it yours:” Overlays don’t (and shouldn’t) really “know” who you are. And you don’t really get to make an overlay your own, either. Even the idea of making a single website your own seems absurd. Websites are like other people’s houses: they are definitely someone else’s space and someone else’s curation of information and content. But a computer that you own should work for you. I want to personalize my machine so that when I go to a website, it works they way I’d want it to. This is also why a video game can be personalized too: you buy the game; it’s yours. That is enough of a reason to want to personalize it.

Personalization isn’t inherently or necessarily about ownership, of course. It doesn’t require something to be owned. Ownership is just one way that we frame personal things in our larger culture and society, since capitalism often frames our relationships to things in our lives.

And my point here is simply that qualities we often discover through ownership are specific kinds of human-artifact interactions that precede modern economic theory like capitalism: we like to make things we interact with often fit who we are and what we do. There is a longitudinal thing that happens when something becomes “ours:” we gain a degree of exclusivity over the use of that thing. That affords space for us to adapt it more to ourselves, our interests, and our needs over time. I wrote about our longer relationships to technical artifacts (in particular) in my love letter to deep systems.

So it’s persistence that really matters: persistence of a thing, the continued presence of something situated with us in our lives, is where we derive the desire to personalize. The more we encounter something, the longer we spend time with it, and the more we gain a sense that it belongs to us and our identity and experience of the world, the more we will be driven to personalize that thing.

The ontology of what makes something personal to something else is grounded in a relationship. Personalization, then, should be founded in a meaningful, persistent, and existing relationship that someone has with an artifact or experience.

This is why in my work on Softerware, we argued that we need better infrastructure. Right now, our infrastructures primarily concern themselves with scale. But we need infrastructure that is also concerned with care, agency, and convenience. This is why our computers and devices, and ultimately our bodies, should be where all of the options we find in an overlay should exist. The closer our artifacts are to our agency and the more opportunities exist for those artifacts to provide care and convenience, the better of a candidate that thing becomes for softerware.

And ideally, we have a “profile” or “agent” in an ecosystem: a system either learns to adapt from us or we tell it something about ourselves. This profile or agent then can persist across devices and every application and experience we encounter.

And that way, every website we visit isn’t asking us what we want, instead websites just listen to whatever we have already established.

We need to fight against this pattern of de-personalization

Personalization has been co-opted, appropriated even, by modern overlay companies. They dismiss the real labor involved in making something accessible and put the burden on every website visitor to fix that website’s problems.

Imagine walking in to a dysfunctional restaurant that has a big sign on the door: “make it yours.” Wow, you think to yourself, that is just like Apple!

But when you walk in, the restaurant is a cold, empty room. Someone approaches and asks confidently, “Welcome! We offer you nothing unless you ask for it. What do we need to do to make this experience yours?”

And then you tell them that you’d like to have food served to you in exchange for money (shouldn’t this be obvious? you think to yourself).

They seem to require thorough instructions to do anything at all. So you tell them that in order to eat and enjoy their food, you would also like to have a table to sit at (which should be cleaned), a chair to sit on (which should be sturdy and comfortable), and you will require a fork, spoon, knife, and napkins, as well as a water served to you when you’re seated.

To your surprise, the restaurant brings out a plastic table and gives you flimsy plastic cutlery. They give you scraps of wood and a plastic chair with a broken leg. They clarify: you can use the wood to “make the chair sturdy, as you requested.” They smile and wink at you, proud of themselves for coming up with this solution to your “sturdy chair accessibility needs.” The water they serve you is unfiltered and metallic from lead piping; it looks brown. Then they place on the table all of the ingredients you’d need in order to cook your own food and leave you to “make it yours.”

This example is what web overlays feel like. They market themselves as personalization, as the future of web accessibility, but really just hide deeply inhospitable dysfunction. User choice is marketed as empowering, but really it is a guise for the fact that websites don’t want to do anything at all for you unless asked, even things that should probably be a bare minimum.

And I want to argue that some of the web should remain a little impersonal. Aside from social spaces, like social media, the web really is a collection of spaces that belong to others. Despite this impersonal foundation for much of the web, it should still strive to be caring and convenient: website owners should provide a hospitable environment (be as accessible as possible by default) and then just do the things we’ve asked of them after that

We need a foundation before “make it yours” becomes a useful motto anywhere. “Make it yours” doesn’t work when the thing we’re talking about is miserable to begin with. This is exactly why I chose to work with Highcharts for my softerware project instead of a visualization library that had no accessibility at all. (There is third-party research that shows Highcharts is the best of the best, when it comes to accessibility.) Highcharts has at least done the minimum (arguably also above and beyond) when it comes to care and convenience for users with disabilities. And so that means that an exploration of softerware with Highcharts can avoid exploring how users patch up garbage and really get to the heart of personalization and agency.

I do believe that pretty much every option modern overlays have available are useful to someone out there. And that is what makes them so deceptive! The idea that we could have personalized experiences on the web is actually forward-thinking. But instead of delivering on forward-thinking and future interfacing with the web, overlays really only accomplish two things: They enable websites to remain uncaring and inaccessible, and they put a significant burden on their visitors.

Well actually, overlays do accomplish a third thing (and perhaps this is the most important one of all): they make overlay companies a massive amount of money.