A love letter to deep systems

The more I think about myself and why I do the things I do, the more I recognize that I love systems with depth. I love systems specifically that enable possibilities through constraints. This is partially why I like numbers or visualizing data, but more to do with why I love games and tool-making.

Most quiet moments I get to stew on things, these sorts of thoughts crop up: “Why do I love visualization toolmaking?” and “Why have I spent the majority of my life designing tabletop rpg systems that about 20 people have actually been able to thoroughly enjoy?” Both have answers in systems.

I love systems that have depth to them. And I love how systems can enable people to do things that they otherwise wouldn’t have cared about or been able to do otherwise. Systems create spaces of possibility through our interaction with them in the same way that Huizinga wrote about the “magic circles” of play and games.

Some people love depth in their tools and systems

There is something about long-term relationships between people and systems that is really satisfying to me. Players of my ttrpg will learn the ins and outs of character building, optimizing turns in combat, and treasure-hunting. I designed my subsystems to be deep, expansive, and rewarding to encourage this long-term strategization. I’ve been honing my game for years! It’s on version 7+ and I’ve got at least two whole books (more than 450 pages) that my players have purchased as well as the core rulebook that I use (with another 150 pages or so). This is a project that has become a love of how people learn to play with systems over decades.

And in toolmaking (which is what I do professionally, since the game-making thing is just a hobby) I recognize that many people actually love tools. And people also will often resist new tools. For example, because I do a lot of consultation work with professionals in the realm of accessibility, it is clear that many who specialize in something like data visualization or interactive data science don’t want to learn a new tool in addition to learning a domain like accessibility. People often prefer to make their existing tools work. I’ve seen this behavior in all kinds of other communities too: like the “js in html” movement or using python to do things with a web frontend that are an affront to god.

Actually, my Data Navigator project was intentionally designed with this kind of resistance in mind. It was designed as a system that could integrate into other systems. And I wanted this to be a tool with immense design potential + depth. I expect folks won’t do cool things with it right away, but in time we might see some really curious stuff emerge!

Over time, we want to be able to change our systems

A lot of studies and design philosophies for interfaces and systems seem short-sighted to me. These short sighted studies reward faster interactions and quick paths to reach simple outcomes. This makes our interface systems shallow. But I love how people become accustomed to systems and adapt and optimize their behavior. People gain a sense of preference over time. They change their tools and their tools change them. Marshall McLuhan wrote on this, “We become what we behold. We shape our tools and then our tools shape us.” I’m especially interested in how this happens to us over time.

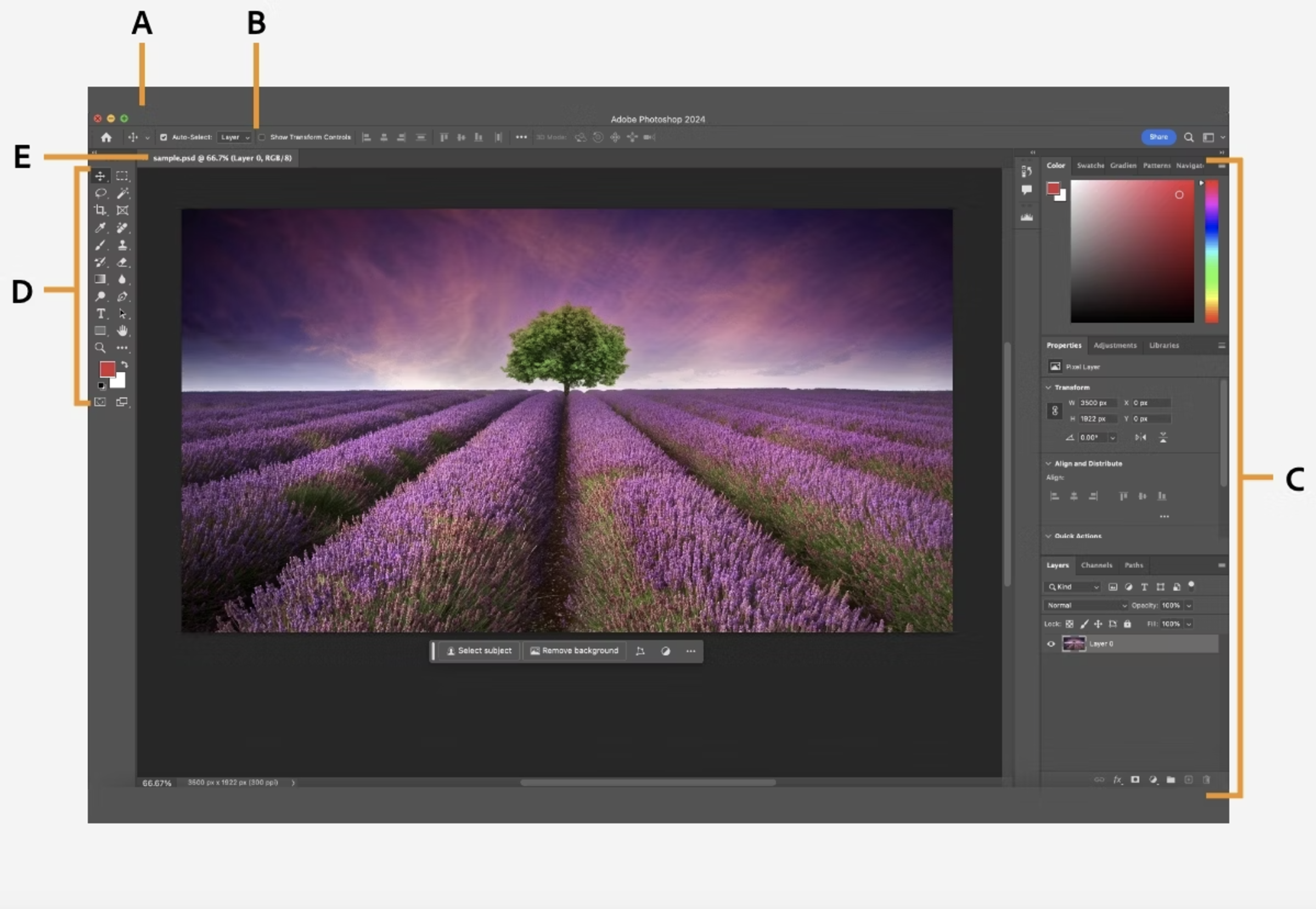

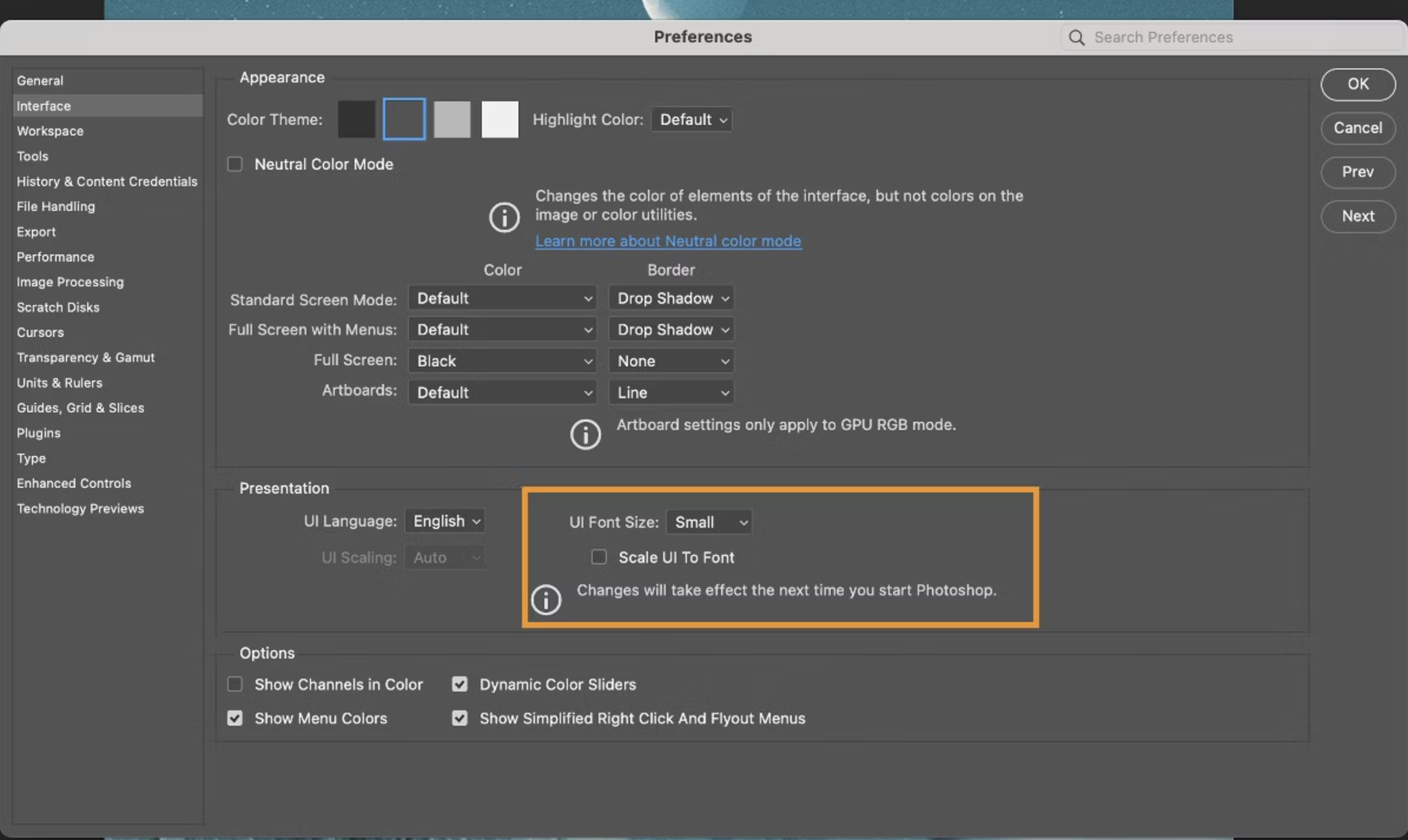

Some people like these longer-term relationships with systems. I know that I do. I still use vanilla javascript for this reason, as offensive as that has been to many people over the years. But this long-term enjoyment of a system or tool feels akin to how some talk about tools of craftwork and how folks will grow sentimental to the tools they’ve used for decades. From a work perspective, it is hard to design a research study (unless it is really longitudinal) around how people embed themselves into systems. But I love systems that are designed with long-term, deep use in mind. Some video games have this built in, but tools like Photoshop do too.

The interface of a tool like Photoshop is immensely deep and complex. It can take a decade to learn the ins and outs of everything it can do and what is useful to a beginner or short-term user might influence the design in a direction that a longer-term, deep-expertise user might not prefer.

The more people like to use a system, the more that they may want to personalize or customize it. They might recognize that the default design behavior or appearance of certain things isn’t quite what they’d like it to be. And one thing that I’ve learned from long-term use of systems is how much pretty much anybody who has committed to a tool or system likes to do this. From specialized equipment in workplaces, to user interfaces in gaming and software, long term use always involves a mix of adaptation of the user and the system.

And our systems and tools can change us

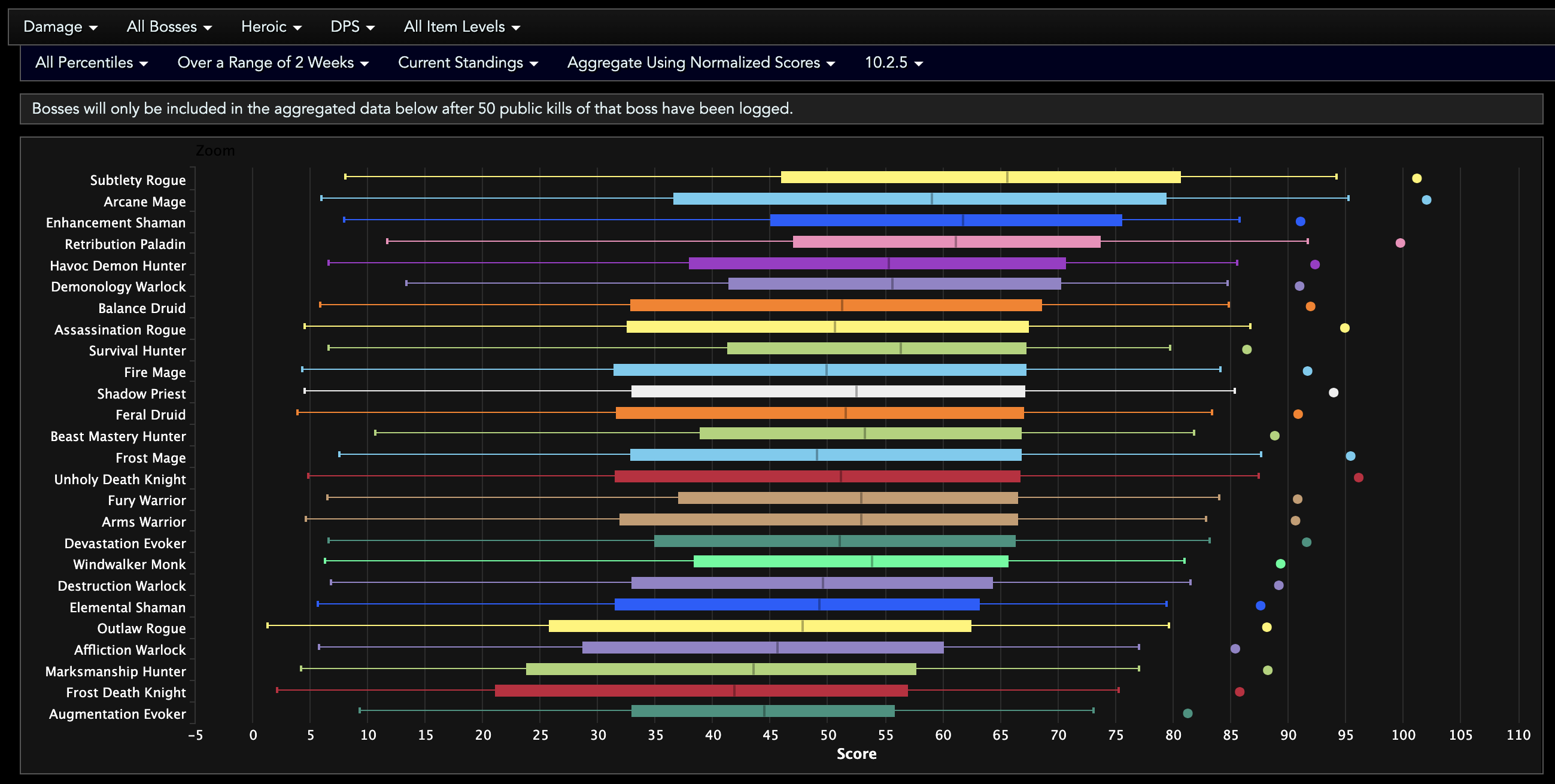

People don’t just make adaptations to their systems and tools but also can adapt to fit systems over time. I have a blog post draft that has been in my drafts since early Spring of this year (2024) about how I learned to “parse” well in raiding in World of Warcraft. It has a lot to do with learning optimal behaviors, understanding how the mathematical systems work, and also understanding how others (who you compete against) use the systems and tools available to them.

Hitting number one was a pretty big deal for me! I beat out people who play World of Warcraft professionally and I did it by “pugging” (which means to play with random people on your team, a significant disadvantage). I felt really good about myself at the time.

And this news seemed like a fun thing to announce to folks who might not know this side of me, too. But as I was drafting this announcement, I kept putting it off. I stewed on it for weeks (and eventually months). My draft kept growing and changing and I kept explaining the context behind it, what the game was about, and all sorts of different details. But I noticed that I kept wanting to explain my favorite part of this victory: how I carefully came to understand how the combat, parsing, raid mechanics, and other systems worked so that I could take that top spot. Vying for the number one spot changed how I play. I grew.

A few times a week I was running analytical simulations, reading complex reports, checking in with fellow competitors and optimizers, literally making spreadsheets and writing custom code, all so that I could find what optimal outcomes were possible. And I learned how to play the game a particular way because I came to know the system more and more at a deeper level. I even took the top spot intentionally on the final day of the season, so that nobody would be able to beat me in subsequent days. It was a very dramatic time in life for me and my small group of friends who I play with online.

Sometimes we hack our systems and tools because we love them

While I haven’t quite locked in on what I want to talk about in that draft yet, it now makes me realize that my love of gaming is often about my love of the systems underneath that game. How do the mechanics work? How do the numbers work? How can I optimize and engineer for a perfect outcome? I love video games and franchises like Balatro, Vampire Survivors, Fallout, Elder Scrolls, Dark Souls/Elden Ring/Bloodborne, and more largely because there are math/mechanical subsystems underneath the game that I love to mess around with and challenge myself to beat or overcome.

So, I think I’m in love with systems and how systems make us feel when we use them over time. I love my own relationships to complex, challenging things that I can take my time with. When data visualization practitioners devote their entire lives to a singular craft (visualizing data) instead of rotating around and picking up whichever new technique or tool is cutting edge, I get interested. I love knowing about specialization and folks who intentionally choose deep expertise over broad exposure. I especially love to hear when folks stick with an “underdog,” like how I have loved playing an Arms Warrior for almost 2 decades or how someone still chooses to use matplotlib in python even though far more expressive or easy-to-use tooling has emerged.

The tools we use and the systems we interact with mean a lot to us. We may not always even make practical decisions with them or about them. I think that is beautifully human to admit! (That being said, I also love how people adapt systems that are not always practical into more practical things. Take how Chris DeMartini made keyboard navigation of visualizations possible in Tableau well before it became part of the software by default. That takes serious dedication and a deep love. You cannot hack a tool to improve it without some degree of appreciation for that tool!)

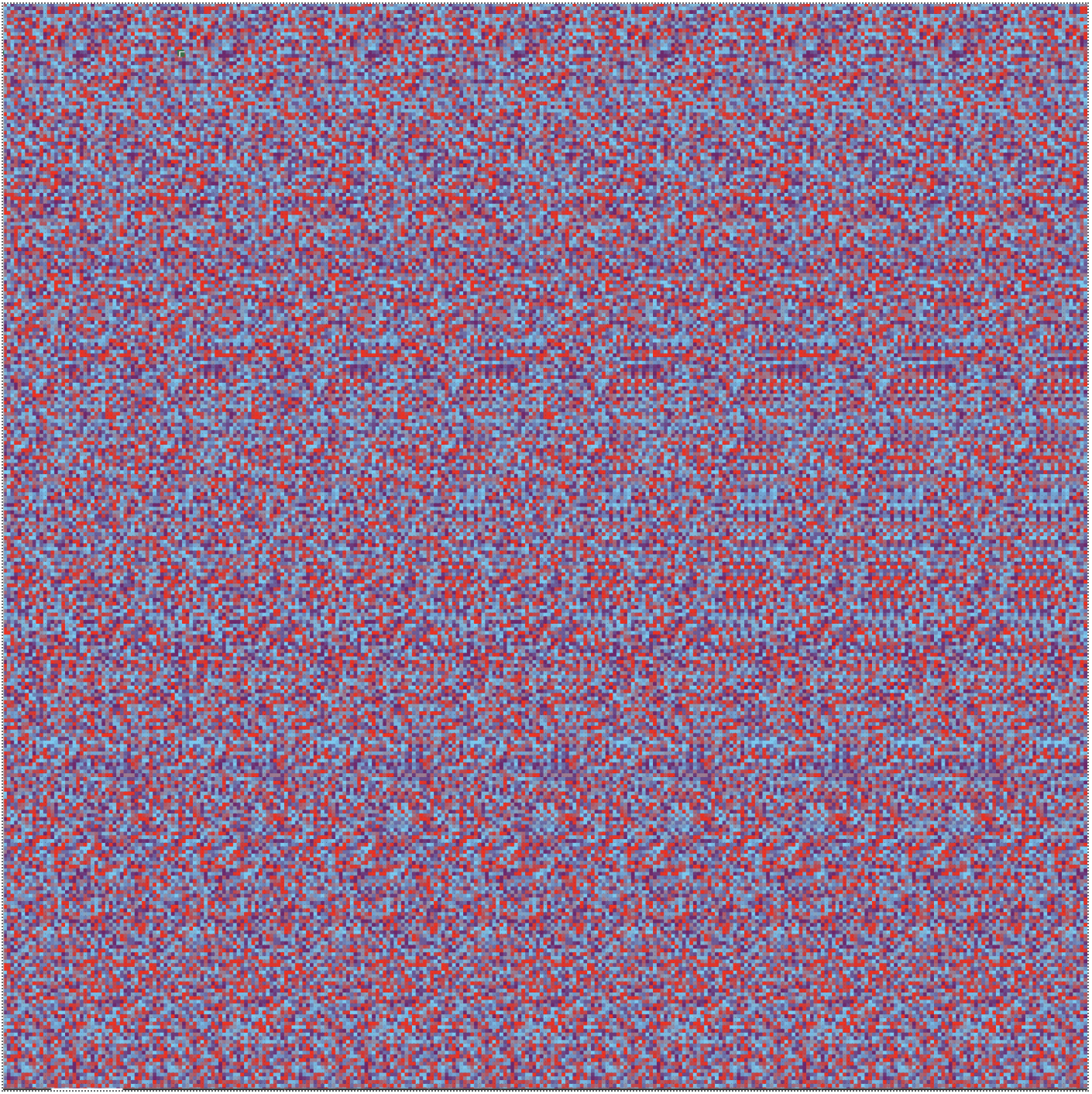

One recent example of hacking the systems we love to do cool things (really recent, posted the same day as the first draft of this blog) is by Dave Richeson, Making a “Magic Eye” image using Excel.

But we love our tools and systems and seeing what they can do, how far they can go. In a way, this is a sort of play of its own kind, separate from the play (or work) intended by tools, systems, and games we interact with. Some scholars call this “emergent” activity or “generative” use of tools. “Generative,” I’m now thinking to myself… “we’ve come a long way in just the last 3 to 4 years thinking about what that word means.”

Scarcity and constraints are sources of creativity and expertise

I have a dislike of large-language models (LLMs) for reasons that are related to why I love these deep systems. We have a whole array of tools we call “generative” that are made possible by LLMs. And while I won’t really unpack why I don’t think they’re actually generative in any meaningful sense, I’ll at least talk about why I dislike the experience I have using them.

To me, LLMs represent all the benefits of a shallow relationship with a system and nothing else. Perhaps tooling will improve around LLMs down the road but at its core, I love being able to take past lessions from doing something, apply that to my current context, inspect the outcomes, and learn. The more deterministic the system, the richer the complexity, and the more robust the potential to refine, the better. But LLMs don’t offer that feeling of certainty-over-time you get from the process of working within a deep system. They instead always offer a degree of uncertainty that ends up not mattering (like, who cares if a prompt always returns slighty different outcomes, you can just produce a billion things and then just pick whatever is good enough). They have a sort of transient cheapness to them that just doesn’t interest me.

David Pye writes about uncertainty in “The Nature and Art of Workmanship” and I think that there is something to me about certainty gained a posteriori that is where I learn to love my tools and systems. I start with a hypothesis or conjecture within the uncertainty of my work and then use tools and systems and games to test them. Afterwards, I can (to some degree) evaluate my hypothesis through the process I chose to employ. But LLMs offer no such testing, evaluation, or inspection. The system is a massive, black-box model of virtually all human language in existence. Prompt “engineers” are really more like prompt “sooth-sayers” in this sense. Knowing with certainty that a particular approach or method is repeatable doesn’t exist with LLMs. They use a large scale and multitudes of failure to approach ideal outcomes. These are not systems that I care to use repeatedly over time because I simply get bored of them.

Again: my love of systems lies in constraints. And constraints are, in a sense, an intentional scarcity of options. Systems that I love thrive when given fewer choices than infinity. LLMs offer the illusion of infinity.

I love having a sense of control, gaining a posteriori feedback about my assumptions, and then developing a sense of predictive power over the systems and tools I use and play with. This is a big contributor to why I love using the same tools over and over. The more I hypothesize, test, and learn, the more I gain a close relationship to the tool. My behaviors change. My needs from the tools change. I adapt the tool and it adapts me. I can measure my past self against my present self if the tool remains with me. I can measure the past tool against the present tool if I have remained with it.

But LLMs carry a sort randomness and lack of control to them. LLMs are tools for delegation and management and despite appearing to offer infinite, limitless potential actually homogenize our creativity at scale.

Pye mentions in his piece on workmanship that there is always a risk that the worker will ruin a job or mess up whatever they’ve set out to build or do. Pye doesn’t really expand on the economics here, but messing up matters because resources are finite. Tools and relationships to people don’t last forever. So this economic force behind risk drives a person to pursue excellence. A person seeks to become good at something because there is risk involved when you’re bad at something. Making fewer mistakes results in less waste, happier customers, and longer-lasting tools.

But as a result of working within a space of deep constraints, the worker gains skill. This is where things get interesting. That skill can then provide a means for creatively exploring in ways that may never have been explored otherwise. You need to have a knowledge of how something works at a deep level in order to hack it or make it do things that previously seemed impossible. Once you gain a certain amount of that depth of expertise, you learn how to do things that seem like pure magic to the uninitiated.

But in contrast to this, LLMs offer magic without any risks for failure. The economics of an LLM are intentionally made into a fantasy. The very real scarcity of rising energy demands across the globe are occluded and hidden, made invisible to the user. And the risk of failure in a prompt is non-existant because prompting is cheap. You can just prompt again. An LLM is designed precisely with the shallowest, most short-term, zero-risk use-cases in mind. My conjecture here is that LLMs don’t encourage any sort of deep expertise in their use and don’t just homogenize creativity but will eventually suffocate and atrophy our collective creativity over time. I reckon that in 20 years we will be less creative and have less of that deep expertise I love because of LLMs. We will see.

Perhaps I should write more about what exactly makes for a good system

So now that I’ve been stewing on all this for a while, I’m getting a sense of what a future blog post should be about. I think that I need to write about what makes for a good system, but focus purely on my opinions and subjective preferences. I should write more about which systems I love and why. I reckon that even though the world seems to still be enamored by LLMs and whatever new thing is out, there might be more folks out there like me, who spend their time loving for, optimizing, maintaining, improving, and hacking the existing deeper systems and tools they love. Expect this post to come out eventually (when I can sneak some time in from my current deadline schedule).