Early design and play-testing for my text adventure game called Streetrat

I'm making a text game where you play a street urchin who steals things. I also wanted to know what people thought of it, so I did some play tests.

In my class “Programming for Game Designers” (which I am taking for fun as my final course in my PhD), our first major project is to design, code, playtest, and refine a text-based adventure game. We are using textadventures and their visual script editor/IDE Quest for the assignment.

If you’ve never played a text adventure before, we were assigned Jacqueline, Jungle Queen! to play in order to get acquainted. Basically, text adventure games take text input from the player and an interactive story unfolds. Some are designed with multiple endings, others are filled with tricky puzzles to solve. It’s a great format of game.

Seeding our story with a little randomness

Our first part of the assignment was that we were given 3 words that we had to integrate into our story. We were given a noun, which had to be a thing that someone could pick up, a verb which was a command that our player should be able to do, and a location that they should be able to visit. Technically, we all submitted 3 words of our own as an assignment but we were given 3 words (that we didn’t choose) from other folks in the class at random. The 3 words I had to work with were: “pick,” “baguette,” and “valley.”

Our story needed to include the 3 words we were given plus 2 additional verbs, 7 additional objects, and 5 more locations. So, we needed to create a story (and ideally some puzzles) using these core pieces.

I fixated on “pick” as my verb. That can be used in a lot of ways! I figured that “pick” as in choose was too boring and didn’t feel interesting enough. And then, of course, I remembered how much I love stealth games. “Pick” can be used on pockets and locks! So I wanted some kind of sneaky, stealthy, rogue-y elements.

And to me, a “baguette” in the context of sneaking and stealing made me think of Disney’s Aladdin right off the bat. So I decided to make my adventure game about being a poor, wretched streetrat who is looking for a big enough break to escape the city they’ve lived in their whole life.

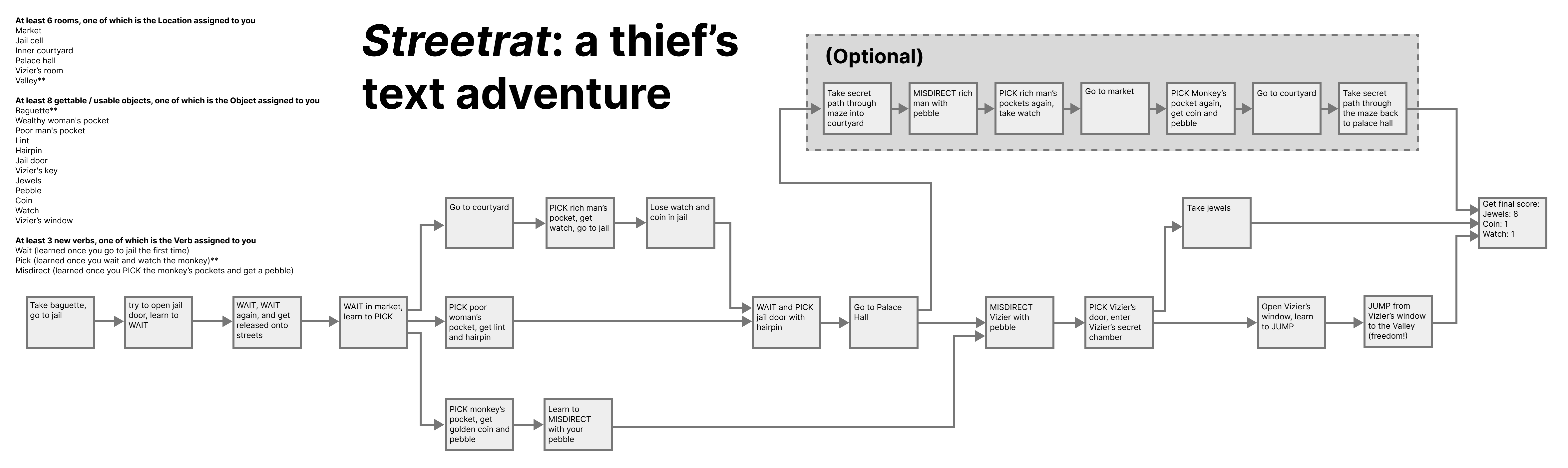

Using a puzzle dependency chart as a way to frame early interactive narrative design

We had to create a “puzzle dependency chart,” which is definitely not a flowchart (according to Ron Gilbert). This kind of chart is a collection of nodes (or boxes), which represent moments that a required action takes place, and edges (or lines) from those nodes to dependent, downstream actions. Writing and sketching out the “shape” of dependencies in this kind of way is really useful! Ron talks all about this in his blog (and he is far more of an expert that I could even pretend to be on this topic).

So a “boring” puzzle/narrative would be linear looking. Like just a box, line to another box, line to another box, and so on. You don’t want that! This exercise is to visualize your narrative pieces in order to get a sense of whether your story is varied enough (when viewed at a high level). You want some branching moments, some parallel paths, some convergence, etc. It is a great tool for early narrative design because it helps you ensure there are enough pieces to keep things interesting, trim excessive or tedious pieces of a process, and also easily reorganize or move nodes around.

Making moments that a character takes an action as a node in a graph helps to abstract the design process so that you can feel the flow of a puzzle/interactive narrative experience at a high level.

Here’s mine:

Long description (read more)

Streetrat: a thief's text adventure

At least 6 rooms, one of which is the Location assigned to you

- Market

- Jail cell

- Inner courtyard

- Palace hall

- Vizier’s room

- Valley**

At least 8 gettable / usable objects, one of which is the Object assigned to you

- Baguette**

- Wealthy woman's pocket

- Poor man's pocket

- Lint

- Hairpin

- Jail door

- Vizier's key

- Jewels

- Pebble

- Coin

- Watch

- Vizier’s window

At least 3 new verbs, one of which is the Verb assigned to you

- Wait (learned once you go to jail the first time)

- Pick (learned once you wait and watch the monkey)**

- Misdirect (learned once you PICK the monkey’s pockets and get a pebble)

Graph Overview

The narrative is linear at the beginning and then splits into 3 branches, two which converge at the same point and a third converges into that branch at a later point. A large optional, linear narrative branches off of the graph and later rejoins at the very end. The end of the main (non-optional) narrative splits one more time before joining back at the end of the story.

Graph Walkthrough

I'm not sure how best to describe a non-linear structure, without using something like my Data Navigator project (which is designed literally with non-linear data navigation in mind). But that being said, I'm going to describe this chart from the ending to the start, since it is about dependencies. It's easier to talk about dependencies in reverse order like "this thing depends on this other thing, which depends on this other thing," and so on.

The ending

The game ends with a scoring screen: 8 points for jewels, 1 for coin, and 1 for watch.

The ending has three dependencies:

- The optional, bonus part of the game, which involves taking the secret path, misdirecting the rich man, picking the man's pockets and taking the watch, going to the market, picking the monkey's pocket, going to the courtyard, and then taking the secret path back.

- Taking the jewels

- Opening the window in the vizier's room and jumping out, into the valley below

The optional part of the game

The optional part of the game only has one dependency:

- Wait and pick the jail door with the hairpin and then go to the palace hall.

Taking the jewels and opening a window in the vizier's room

Taking the jewels and the 2-part branch of the narrative where you open the window and jump out in the vizier's room share only one dependency:

- Misdirect the vizier, go to the vizier's secret chamber, and find the jewels.

Misdirecting the vizier

Misdirecting the vizier has 2 dependencies, the first is shared with the optional part of the game:

- Wait and pick the jail door with the hairpin and then go to the palace hall.

- Pick the monkey's pocket, get the coin and pebble, and learn to misdirect with the pebble.

Waiting to pick the jail door

Waiting to pick the jail door with the hairpin has 2 dependencies:

- Go to the courtyard, pick the rich man's pocket, get the watch, go to jail, and when in jail have your valuables get confiscated.

- Pick the poor woman's pocket and get lint and a hairpin.

Going to the courtyard to pick the rich man's pocket, picking the poor woman's pocket, and picking the monkey's pockets

These three branches all share the same, single dependency (which is the start of the game). The start is a single linear process:

- Take the baguette, go to jail, try to open the jail door, learn how to wait, wait twice, get released out of jail, wait in the market, learn how to pick pockets.

Building a prototype

So I built a first pass of the game in Quest, which took me far longer than I thought. It’s a visual code editor, so rather than just writing code as text, there are dropdowns and pre-chosen units of logic written that help you assemble the game easily.

That being said, it does take a little getting used to!

I made sure that my working prototype allowed someone to play the whole game from start to finish and included rich narrative descriptions when the user chose to inspect (“look at”) every object, person, and location in the game.

Play-testing

Play-testing is an obvious step at this point in the game’s design. Play-testing is when you bring in someone (or a couple folks) to play your game. You watch them play but it is important that you don’t give them hints or say anything to them to guide them. You are a silent, distant observer. You take extensive notes during the play-test and afterwards spend time asking follow up questions.

Designing questions for the play-test

It can be helpful to frame questions for your play-test before you actually have the test. Thinking about what you want to learn from players is really helpful. I think about these kinds of questions in 2 ways:

- open-ended, exploratory, and qualitative

- as a testable “hypothesis” (not actually framed in an experimental way, mind you - that’s a proper hypothesis without the quotation marks!)

In human-computer interaction research we might refer to the preparation of “questions” like these beforehand as structured interview questions. That is, we have a reason for asking specific questions and we want to ensure that we (at least) ask these questions.

But also: part of observational work involves seeing people do things that raises new questions. Writing these down so that you can get to them later is where we get semi-structured interviews from. (Of course, the methodology is a bit more nuanced than everything I’ve just said here, but this is, at a high level, the spirit behind these approaches at least.)

Core questions

- Is it fun to play?

- Does it accomplish the vibes I want?

- Are people able to solve the puzzles and progress the story?

As a designer, I wrote the story. I can easily beat my own game. But did I leave enough hints and breadcrumbs? Did I design the story with enough yellow paint? And also: am I too heavy-handed with my hints in a way that might ruin or spoil the fun of this kind of game?

I think the most important part of this game (and any game) is that it is actually fun. Puzzle games in particular rely heavily on signposts, hints, affordances, and invoking patterns in our pattern-recognizing brains. So to make the game fun, I need to strike a balance between giving the player the correct tools but also not telling them exactly how to swing a hammer. Experimentation in a puzzle game is key. Avoiding punishment is important because that will increase the player’s perception of risk and then incentivize them to experiment less.

I want to design a game that feels like you can safely experiment. So part of the design of my world, which involves a streetrat who steals things, is that you do get in trouble. But the trouble you get into just involves a temporary stay in a jail cell. And in fact, the jail itself should be seen as a possible hurdle to overcome later. In jail, the player is shown two things. First, that there is an exit that they cannot reach (they are told they can go west, but not as long as they are in a locked cell). That hints they can eventually go somewhere new. Second, after attempting anything a few times, they will be shown a new power: waiting. Waiting allows them to “watch for new opportunities” and while they are in jail, their first time waiting results in the jail guard leaving them all alone! But they still can’t solve this puzzle now, so they have to wait again and are eventually released onto the streets.

In my game the hardest puzzle will involve players getting everything they can and then intentionally going back to jail so that they can open the jail door with their new tool and new skill. But my biggest worry is whether folks can actually figure this out!

My play-test hypotheses:

These are my “questions” that I intend to “test” by observing the players and (in some cases) following up with further questions:

- This will be fun for someone who likes getting into trouble, but you probably need to be comfortable with “stealing” and “going to jail for your crimes”

- Someone might not find the game fun if they aren’t familiar enough with text games in general (they can be a bit clunky at first)

- The main puzzle (going back to jail on purpose in order to break into the palace) might be too hard to figure out with the current level of signposting I have

- My mechanics for misdirecting might be too hard to figure out (you need to guess who to target with the pebble before doing something sneaky)

- While I tried to set the vibes with rich descriptions, I might have written too much (or written so many vibes that it overpowers the subtle hints written alongside things)

Discussion/learnings from my 2 play-tests

Observational notes

Was it fun?

Good news: I think the core design is pretty fun. Both players enjoyed getting into trouble, one definitely spent a lot more time than the other trying out verbs that weren’t part of the game like “sneak” and “steal” and “distract” (even tried “distract” before they got the ability to “misdirect”). One of them was much more hesitant about going back to jail, but they actually figured out that they needed to relatively quickly.

She remarked, “I’ve done everything here I think… I probably need to unlock the jail door now. But I don’t want to lose my treasure!” And this was interesting to think about: she perceived a risk in the game (that your stuff gets confiscated when you go to jail) but didn’t seem to mind stealing those things immediately again after getting out of jail. She also said, “I really wish I could stash my stuff so that I don’t lose it again.” Which helped me learn that the re-stealing expectation that was part of the game might be too tedious or boring (after you end up doing it a couple times).

How were the vibes?

Both players enjoyed the textual descriptions and I only found a couple awkward grammar/spelling errors while they played.

It was helpful to hear them each chuckle to themselves at different points when the read something funny or exclaim “woah!” and “wowww!” when they encountered something surprising. It was fun to watch someone essentially reading a book you wrote and getting to experience their reactions as they read it. (As an aside this makes me wonder - do authors ever do “reading tests” to see what people think of the vibes of a draft they are working on? I’d like to imagine that having a group of friends like the Inklings served that purpose for Tolkein and Lewis and the like.)

Could they solve the puzzles?

Good news: they each solved the major puzzle hurdle I was worried the most about. Bad news: one of them ran out of time (in class we only had 20 minutes). I really wanted to have them both finish, but the player who did finish also did the “optional” portion of the narrative (which essentially involves going back and stealing everything again after the guards take your treasure away).

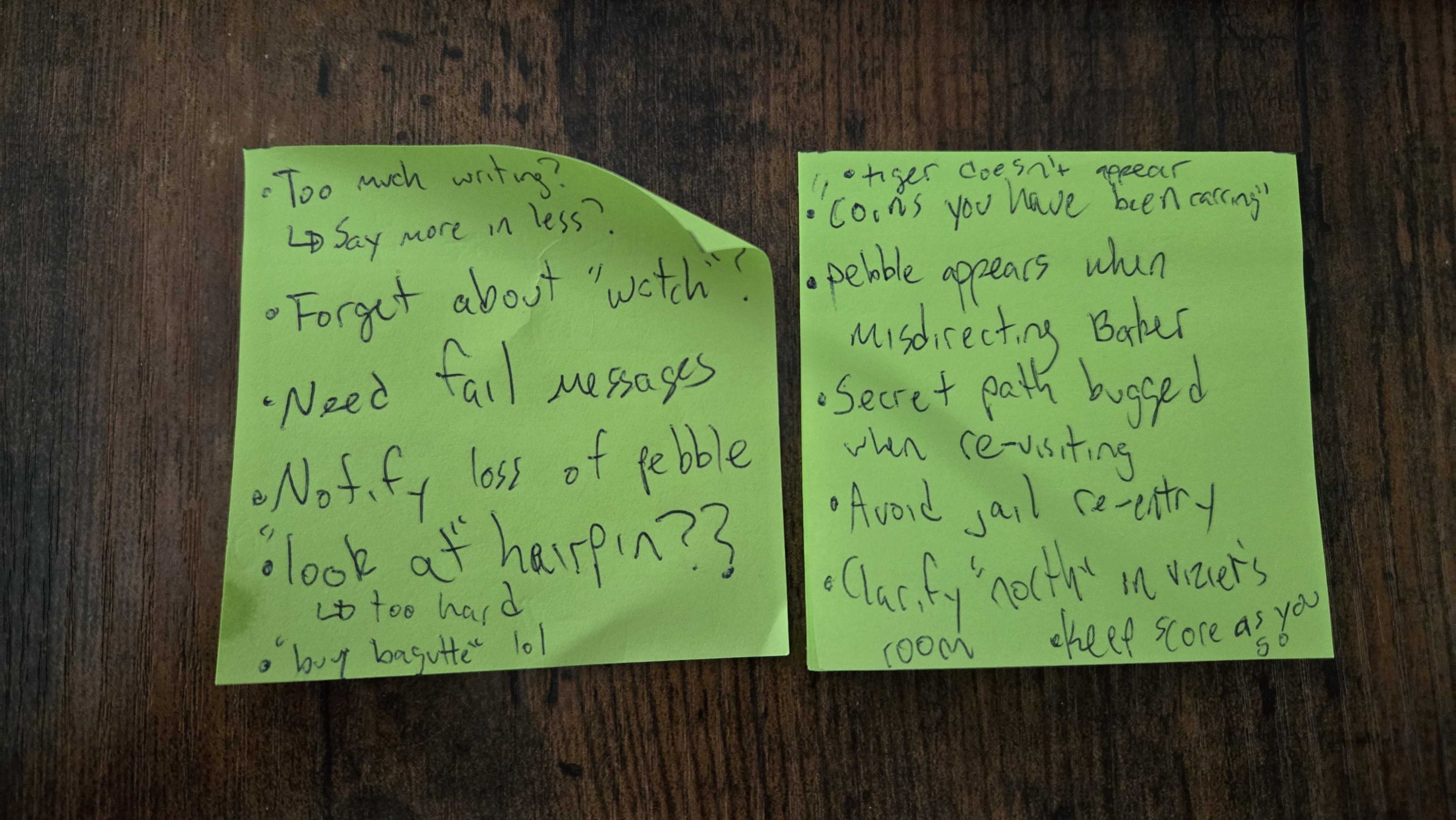

Next steps

I was able to identify a few areas that were buggy, some areas where I could add some smart hints, and also a new feature design: keeping score while you play.

On that last point: During the game, you see “Score: 0/10” the whole time. I added that because I want players to expect to be judged on their performance when the game ends and also to instill the idea that completing the game is not the same as getting a perfect score. But it was unclear what affected that score while they played!

The player who finished got a perfect score, but that was because she (in her own words), “really loves stealing mechanics in games, so I wanted to get my loot back.” But if the score went up while loot was in your inventory and then went back down when the guards confiscated it, it might encourage players to go back and do that optional path in the narrative.

Bugs/typos/mistakes:

- Tiger doesn't appear

- Secret path is bugged (doesn't let you re-use it)

- Jail lets you re-enter it (and takes your items if you do)

- Pebble doesn't return to monkey if you misdirect the baker

- Remove the "take" command from the verb list for the bakery stall

- "Carrying" is spelled as "carring"

Unclear moments/things to improve:

- Would be nice to keep score while you play (even if it goes down in the jail)

- Should clarify what "north" is in the vizier's room

- Need more messages when something fails (like misdirecting)

- Consider alternatives to "look at hairpin" and "look at pebble" for unlocking new abilities

- Give some beginner instructions/tips at the start of the game like: "Try LOOK AT on everything at least once!" "Check your inventory and the scene details often" etc

- Give more feedback when new objects are added to the scene (monkey pocket/poor woman's pouch, etc)

- Notify more clearly when you lose your pebble

- Consider more fun vibes-based interactions ("speak to," "buy," funny failures, etc)

- Maybe add special abilities to the "HELP" command?

Reflection

Overall, it was fun to build a simple game and run some play-tests. The game will be polished a bit more, so expect another (probably shorter) post from me once it is released, so you can play it if you want (although this blog post probably spoiled it quite a bit!).

EDIT: My next blog post is now out! It has details for how to play Streetrat.